Consultation on reforms to public sector exit payments, February 2016

Preliminary matters

Payments made in relation to injury, ill-health or death

Thompsons welcomes the assurance that:

“1.7 Payments made by employers in relation to injury, ill-health or death during employment are outside the scope of these proposals and the consultation.”

However, we are concerned about the suggestion on page 4 that payments relating to death or injury must be “attributable to duty”. Introducing the issue of causation sets up the possibility of litigation with public sector employers seeking to deny liability.

The government promised to exempt anyone earning under 27,000. This has been abandoned. This is a significant narrowing of the scope of the proposals given that the government’s response to the previous consultation was:

“Compensation payments in respect of death or injury attributable to the employment, serious ill health and ill health retirement and certain fitness related requirements.”1

It is our view that £27,000 was a figure which was too low in any event.

Another concern we have is the manipulation of statute law to evade contractual obligations which have been entered into in good faith, and upon which individuals have arranged their financial, social and other planning.

The government needs to make it plain what types of payment are within the scope of the current consultation, and what types of payment are not.

Part 2 of the draft Public Sector Exit Payments Regulations 2016 make it clear that they apply to payments in lieu of notice2 and negotiated settlements under a settlement agreement or conciliation agreement3 , but not to orders of the court or tribunal4. The current consultation concerns "most employer-funded payments made in relation to leaving employment, including compensation packages for exits whether in impending or declared redundancy situations or in other situations where individuals leave public sector employment with employer-funded exit packages" (consultation summary, page 4).

We are particularly concerned that any limits on exit payments could be used to limit the consequences of the government’s own wrongdoing and adversely affect the resolution of workplace disputes.

There are circumstances where an employer is likely to bear some degree of culpability (although we note that in respect of pay in lieu of notice the employer is due to pay that sum whether notice is worked or not). Limiting exit payments is of particular concern in discrimination claims (especially where there is a significant injury to feelings element) and the risk is, it will force litigation in cases where amicable resolution would otherwise have been possible and adds further red tape to the already obstructive process of Treasury Approval of settlements. It also gives the government a mechanism to deny proper remedy against itself.

The inclusion of conciliated agreements will catch ACAS COT3s. It will therefore bring into scope all settlements, regardless of merit, and for some high value claims undermine any incentive to engage with Early Conciliation or settlement negotiations more generally. This runs contrary to the government’s wider obligations by virtue of Article 19 Treaty of European Union and the requirement for Member States to provide remedies “sufficient to ensure effective legal protection” of rights conferred by EU law.

The consultation paper also makes no reference to the review mechanism for the level of any tariff or limit on exit payments or their calculation, such as whether any limit would be index-linked, for example, or if the cap is time-limited.

Tax and national insurance

The consultation paper has not addressed the current or proposed future tax and national insurance treatment of the various types of payment that fall within the scope of the consultation. The summary says that "most employer-funded payments made in relation to leaving employment, including compensation packages for exits whether in impending or declared redundancy situations or in other situations where individuals leave public sector employment with employer-funded exit packages" are in scope. The draft Public Sector Exit Payment Regulations 2016 suggest that payments in lieu of notice and other contractual payments may be included.

Thompsons notes that the Government intends to "tighten the scope of the income tax exemption for termination payments to prevent manipulation5 " and align the tax and national insurance treatment of termination payments so that contractual and non-contractual payments that exceed £30,000 will be subject to tax and national insurance. We also note that these changes will only come into force in April 2018.

If all forms of payment on termination of employment are subject to a tariff or cap of any nature, the tariff or cap must address different tax treatments of contractual and non-contractual payments, at least until the 2016 Budget proposals are introduced. For instance, if an exit payment is capped at three weeks’ pay for each year of service, and if an employee would otherwise be entitled to a greater amount, is it the taxable contractual entitlement which is being withheld or the non-taxable termination payment?

Question 1: Are there alternative options and approaches to compensation provision reform you think the government should be considering? What alternative approaches would you suggest and why?

The government’s 2015 election manifesto pledge was

“We will end taxpayer-funded six-figure payoffs for the best paid public sector workers”

This limit is arbitrary, and although this was pointed out during the previous consultation periods, it nevertheless remains. Responding to this question is therefore restricted by the imposition of that arbitrary limit.

An additional problem in responding is that the extent of the problem remains unclear. Although the figures given in an earlier consultation response6 suggest that in 2012-13 3,452 (4.78%) public sector employees left with a package of at least £100k, there was no breakdown as to the reasons for those departures or the size of the exit payment. For all we know they were all caught by the exceptions proposed in this consultation. We believe these figures are fundamental to making the government’s case that change is needed and the lack of detail flies in the face of the government’s own Consultation Principles (2016) which say:

“C. Consultations should be informative

Give enough information to ensure that those consulted understand the issues and can give informed responses. Include validated assessments of the costs and benefits of the options being considered when possible”

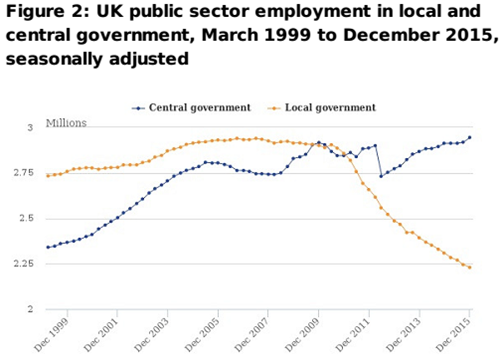

We are conscious too that the levels of exits and payments identified in those figures are at a scale that is wholly exceptional, short term and unsustainable. The context is clearly shown in this ONS graph7. To some extent this is a problem of the past.

We also note that for significant sections of the public sector, provisions already exist for the recovery of exit payments and the need for another limit is not explained. For instance, in the government’s response to the earlier consultation it noted these arrangements are more common where a formal compensation scheme exists such as the Civil Service, NHS and Armed Forces.

One of the rationales for the change, expressed in the consultation, is that it is necessary for flexibility:

“Modernity & flexibility

4.5 Exit compensation terms need to reflect a rapidly changing economy and society, the modernisation and improvement of public services and consequential changes in the public sector workforce. They need to give employees a reasonable degree of certainty over their potential entitlements. However, there also needs to be a considerable degree of flexibility in setting those entitlements and any related limits, so they can be readily updated to reflect overall changes in the structure and financing of public services, in the size and make-up of the various workforces and the broader fiscal environment.”

Employees already have a ‘reasonable degree of certainty over their potential entitlements’ so we presume that this is more about ‘flexibility’. Sadly ‘flexibility’ is now a euphemism for pilfering from agreed redundancy arrangements at will, when redundancy payments were originally intended as something completely different in this context, namely to facilitate organisational change, and to ameliorate the effect of that on displaced staff.

The question seeks views on alternatives. One was pointed out during the questioning of Jeremy Hunt MP by the Health Committee on public health spending,8

Q265 Barbara Keeley: You have rehired 17% of the people who were made redundant in the last three years, according to the figures the Department sent us, and that is a very substantial proportion; 17% have been taken back on again, a number of them within 28 days, ridiculously enough, and most of them within one year. That smacks of appallingly bad planning—that they were not able to be redeployed from the role you were moving them out of into another one. It smacks of carelessness with public money.”

Joined-up government would have a better approach to redundancies and redeployment by way of cross-department communication, as well as intra-office and intra-team communication.

Question 2: Do you agree with the proposed approach of limiting early retirement benefits with reference to the cost for the employer? What alternative approaches would you suggest and why?

The proposal to limit early retirement benefits with reference to the cost to the employers is inconsistent with the commitment made to public service pension scheme members which is reflected in the consultation paper, and existing pension scheme regulations.

Paragraph 7.13 of the consultation paper says:

The government would ensure any reforms do not breach the provisions of the Public Service Pensions Act 2013 on changes to pension schemes for 25 years (the 25 year guarantee): employees would remain entitled to pensions they have accrued during their employment.

This reflects a commitment made to trade unions when the public service pension schemes were reformed, as repeated by the Secretary to the Treasury in the debate on the second reading of the Public Service Pensions Bill:

Our aim was to strike a deal that would last, unchanged, for 25 years. Talks with the unions took place on all elements of that deal. I should stress that the Government did not do all the talking in those meetings—we listened carefully, too. Agreeing the design of these pensions has taken a considerable cross-Government effort over the past 18 months. The Minister for the Cabinet Office, the Home Secretary, the Lord Chancellor, the Education Secretary, the Defence Secretary, the Communities and Local Government Secretary and the former Health Secretary worked hard to understand the concerns of the trade unions and member representatives in their sectors9.

The regulations made under that Act contain provisions relating to the early payment of pensions in the event of the termination of employment on the grounds of redundancy or business efficiency. For instance, regulation 30(7) of the Local Government Pension Scheme Regulations 2013 says that if a member is over the age of 55 and is dismissed or retires by mutual consent on such grounds, he or she is entitled to an immediate and unreduced pension. Regulation 82 of the Public Service Pensions (Civil Servants and Others) Regulations 2014 says that if a member is over the age of 55 and is dismissed or retires by mutual consent on such grounds, he or she is entitled to buy out any actuarial reduction using their termination payment, and if it is insufficient, his or her employer must make up the difference. There are similar provisions in the other public service pension schemes.

These rights to an immediate and unreduced pension may not be removed unless the Government intends to renege on the 25 year guarantee.

In answer to question 2, therefore, cost to the employer cannot be the only determining factor for limiting early retirement benefits. The promises made by government when the public service pension schemes were reformed must be taken into account. The NHS model cannot be adopted for employees in local government, the civil service, or elsewhere in cases where the regulations made under the Public Service Pensions Act 2013 grant an entitlement to an employer-funded pension top-up.

Prohibiting top-ups entirely – we repeat the points made above regarding the 25 year guarantee promised when the public service pension schemes were reformed. Prohibiting pension top-ups would be inconsistent with these promises.

Parity of treatment with the private sector must also be observed. The consultation notes that:

“Fairness

4.3 … it is important that a fair and appropriate level of compensation is provided for employees who are required to leave public sector jobs. It is also important that the level of compensation is seen as fair and appropriate by taxpayers, who ultimately fund these costs. The government therefore believes that compensation arrangements in the public sector should be considered in the context of normal compensation arrangements in the wider economy.”

The consultation has offered no evidence as to what ‘context of normal compensation arrangements in the wider economy’ actually is.

There was no proposal in the 2016 Budget to change the tax treatment of employer or employee contributions to an occupational pension scheme when paid shortly before the termination of employment.

The consultation paper fails to address a major difference between (i) employer- or employee-funded pension top-ups and (ii) other payments which may or may not fall within the scope of "exit payments", which is taxation. In the private sector, sensible tax-planning by the employer means that an exit payment is more affordable if it is paid in the form of a pension top-up.

We recognise that the consultation addresses the cost to the taxpayer of funding public sector exit payments, and that includes the fiscal effect of allowing pension top-ups paid by the employer. But it also seeks to ensure consistency with the private sector. If private sector exit arrangements will continue to allow tax-advantageous pension planning at the point of the termination of employment, by allowing a termination payment to be used to fund a pension top-up, the same should apply equally in the public sector.

This is a point which goes wider than ensuring equality of treatment between the public and private sectors. The Government has an interest in ensuring that pension saving is adequate, and the possibility of using a termination payment to increase pension is most likely to be attractive to older workers whose pension arrangements have not been adequate.

The Government should recognise that pension top-ups are of a qualitatively different nature from other forms of exit payment. It is not appropriate to treat them in the same way and include pension top-ups within the scope of the consultation.

Changing the early access age – The age at which a pension scheme member is able to access an early retirement pension relates to their future employment prospects, not their longevity. A 55-year-old public servant with limited chances of obtaining further employment will need to access his or her pension. That does not relate to how long they are expected to live.

Some employments – the police, firefighters and the armed forces – were given special protection when the Public Service Pensions Act 2013 was enacted, in the form of a lower normal pension age. It must be recognised, however, that there are other public sector employees who have a normal pension age equal to their State pension age but who work in occupations which involve hard physical labour, which take a toll on the individual. In those circumstances early access would be appropriate, and the rise in the minimum age at which an immediate but unreduced pension can be drawn would be inappropriate.

Again, parity of treatment with the private sector must be taken into account. If a private sector employer is able to make an employee redundant at the age of 55 with an immediate and unreduced pension, why should that possibility be eliminated altogether in the public sector? An outright prohibition against early access below a prescribed age would be unduly restrictive.

If this proposal represents another ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach then we would not support it. If a more sophisticated approach applied then we would wish to see those proposals before commenting. In light of the government’s promises about early access due to fitness in certain physical occupations we consider that those should be covered by exemptions.

Question 3: Do you agree with the proposed options around capping tariff terms? What alternative approaches would you suggest and why?

Paragraph 4.10 of the consultation limits this to the calculation of redundancy payments only. Paragraph 4.11 adds that

“The government is therefore considering setting maximum tariff terms that can be offered to ensure there is greater fairness and consistency across different public sector workforces.”

Consistency is not synonymous with fairness and this ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach needs to acknowledge that. The consultation goes no further than noting a difference of approach, without seeking to understand why those differences occur. We presume that all will have come about as a result bargaining processes whereby the parties engaged in the usual ‘give and take’ that mark out that process, and it might well be that what looks like one group's advantage is balanced by a disadvantage elsewhere. Unilaterally harmonising terms out of context ignores that narrative and it fundamentally unfair. As those arrangements are likely to have come about as a result of collective bargaining with recognised trade unions on behalf of their memberships we are also concerned about the effect which such an arbitrary measure would have on workplace relations.

We therefore do not agree with unilaterally setting tariffs in the manner suggested.

We have no comment on the proposal in paragraph 4.13 to cap the number of months used to calculate redundancy at 15 months.

We have no comment on the proposal in paragraph 4.14 to cap the maximum salary for calculating redundancy payments, possibly at £80,000 as per the NHS scheme.

We do not understand the nature of the government’s proposal at paragraph 4.15:

“4.15 The entitlement to a lump sum compensation payment for those close to retirement age could be subject to a taper to reflect the fact that there is a shorter period of time between redundancy and eligibility to receive a pension. This could be set with reference to a scheme’s normal pension retirement age (NPA), or where applicable a target retirement age. Such tapering would need to be fair to both those nearing pension age and those above that age who leave with an exit payment.”

We do not understand what the lump sum payment referred to is.

There are references, variously, to redundancy, pension, and an exit payment. We presume that this is a proposal to reduce a redundancy payment for those close to retiring. We do not oppose the principle of such a taper, but the detail is too vague. A redundancy payment is partly to assist the transition from one job to another. For this reason we do not agree that this should be linked to an NPA - being a pensioner is not the same as being retired - many people continue to work after retirement from a primary role and the modern reality is that many will have to. Any tapering should be linked to an actual cessation of economic activity, not a theoretical one.

Question 4: Do you agree that the government has established the correct scope for the implementation of this policy? Are there other factors the government should be taking into account with regard to scope?

Earnings threshold

We are surprised that the government is not honouring its commitment to create exemptions from the scope for employees below a particular earnings threshold. When this manifesto pledge was first announced Priti Patel MP wrote:

“This commitment, which will be included in our 2015 General Election manifesto, will cap payments for well-paid public sector workers at £95,000. Crucially, those earning less than £27,000 will be exempted to protect the very small number of low earning, long-serving public servants.”10

On 2 February 2015, ahead of the second reading of the enabling Act, The Minister for Small Business, Industry and Enterprise Anna Soubry MP said:

“What we do know is that there is a very small number of workers in the public sector on about £25,000 who could be caught by this but those are extremely rare conditions.”11

Despite these pledges, and acceptance of there being a ‘crucial’ issue to address, there is no exemption in the scoping provisions and there should be. We would support the existence of these, and wider, exemptions to reflect the nature of the workforce, their terms and conditions, and the fact that these proposals represent a significant departure from agreed arrangements.

We are concerned that the proposals appear to take no account of the fact that a cap applied in the context of London weighting, or to those earning unsocial hours premiums, will have a very different impact to where those factors do not apply. A similar issue arises in connection with pension fund strain cost estimates are sought before proceeding with redundancies and will then make their decisions on whether such a redundancy will be cost effective. Strain costs are set out by fund actuaries so are different throughout the country whereas the exit cap is a standard rate. This immediately produces a regional disparity that falls foul of the stated aim of fairness.

We are concerned too that there is no attempt to provide any off-set for payments owed by the employee to the employer upon termination. These commonly are training costs or car loans and are payable either over an agreed set period, or not repayable at all after sufficient time has elapsed. If the employer terminates the contract early and triggers payment, or early payment, it is unfair not to account for that in these measures.

Firefighters

Section 2 of the consultation paper says that:

Different provisions apply where [a firefighter] is leaving employment owing to illness or where a firefighter is aged 55 or over, lack of fitness, and these are outside the scope of this consultation.

Section 5 says, however, that the reforms would apply, inter alia, to section 34 of the Fire and Rescue Services Act 2004. It is worrying that it is not made plain enough in the consultation that the existing arrangements for authority-initiated early retirement where a firefighter lacks fitness will not be changed in any way. We note that the then Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government gave this commitment in 2014:

Penny Mordaunt: If someone fails a fitness test through no fault of their own and they do not qualify for ill health retirement, they will get a redeployed role or an unreduced pension. That will be put on a statutory footing in the national framework—a full, unreduced pension, if not an alternative role.12.

There is an obligation on the government to make it plain that early retirement terms for firefighters who are unable to continue working by reason of fitness standards, but falling short of ill-health, will not be affected.

The wider public sector

There needs to be greater clarity as to the workforces which are in scope. The consultation paper makes it clear that public servants covered by statutory pension and compensation schemes are in scope, but section 5 says that "the reforms are intended to apply to the major workforces under existing public sector compensation schemes and other exit arrangements"

The consultation does not address the difference between public servants and the wider public sector. The two terms do not mean the same thing, and the draft Public Sector Exit Payments Regulations 2016 suggest that other workers within the wider public sector, for instance those who work for public financial and non-financial corporations such as the BBC, the Royal Bank of Scotland or Post Office Ltd, might be in scope unless specific exclusions are made.

The government needs to be clearer about its intentions. We suggest that any regulations should give an exhaustive definition as to which workforces are covered, not by referring to bodies within the public sector as categorised by the Office of National Statistics (as the draft Pubic Sector Exit Payments Regulations 2016 do) but by referring to specific employers.

Despite the implication otherwise, there is no explanation given for the specific exclusions in the draft Pubic Sector Exit Payments Regulations 2016, either in this consultation or the government’s last two responses.13 This is a surprising omission when the government is asking about whether the proposed scope is correct.

In the circumstances we feel unable to comment further on this question as there is inadequate information in contravention of the government’s Consultation Principle C.

The timeline needs to take into account the revised tax and national insurance arrangements that will apply, from April 2018, according to the 2016 Budget Red Book. If specific tariffs are to be introduced now, and in particular if pension top-ups are included in any tariff, it must be recognised that the value to any employee whose employment ends of any exit payment will be dramatically different if the payment or top-up is or is not subject to tax and national insurance.

Question 5: Are there other impacts not covered in the above which you would highlight in relation to the proposals in this consultation document?

See earlier responses

Question 6: Are you able to provide any further information and data in relation to the impacts which may be relevant to the government in setting out the above?

Thompsons has no response to this question.

Question 7: Are you able to provide information and data in relation to redundancy provision in the wider economy which could be used to inform the government’s response to this consultation?

Thompsons has no response to this question.

1September 2015 response, page 6

2Regulation 3(1)(d)

3Regulation 3(1)(e)

4Regulation 3(2)(e)

5Budget 2016 Red Book, paragraph 2.26

6https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/recovery-of-public-sector-exit-payments/recovery-of-public-sector-exit-payments

7http://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/publicsectorpersonnel/bulletins/publicsectoremployment/december2015

8Tuesday 17 December 2013, Oral evidence: Public expenditure on health and social care, HC 793 http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/WrittenEvidence.svc/EvidenceHtml/4813

9Hansard, HC Deb 29 October 2012 Vol. 552 Col. 56.

10Daily Telegraph article 3 January 2015, Taxpayer-funded golden goodbyes are just not fair, Priti Patel, Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury

11Hansard HC Deb. 2 February 2016 Vol. 605, Col. 887: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201516/cmhansrd/cm160202/debtext/160202-0004.htm

12Hansard HC Deb. 15 December 2014 Vol. 589 Col. 1167

13“…payments from the following authorities were identified as being potentially exempt in the Government’s response to the consultation on these proposals”